Continuing my Horus Heresy kick, over the weekend I read Betrayer by Aaron Dembski-Bowden. I was a little hesitant to grab this book but did so because it comes up on a number of best-of-series lists, not all of which are reliable (too much focus on action). Turns out though Betrayer is very much possibly the best 40k/30k novel I’ve read, and certainly among the top. Part of this I attribute to Dembski-Bowden apparently being an actual player of the game, something I don’t get from a number of the authors. Not that it’s necessary, but it might bring an extra level of love to the work.

Continuing my Horus Heresy kick, over the weekend I read Betrayer by Aaron Dembski-Bowden. I was a little hesitant to grab this book but did so because it comes up on a number of best-of-series lists, not all of which are reliable (too much focus on action). Turns out though Betrayer is very much possibly the best 40k/30k novel I’ve read, and certainly among the top. Part of this I attribute to Dembski-Bowden apparently being an actual player of the game, something I don’t get from a number of the authors. Not that it’s necessary, but it might bring an extra level of love to the work.

There are no spoilers in these thoughts.

Characters

Here that love’s paid off because he’s done the totally unexpected: Made the World Eaters, Angron, and especially Khârn possibly the most fascinating characters in the entire series. My hesitation about the book was precisely because by the 40th century they never come across as particularly interesting. Mindless killing machines, they do what they say—Kill! Maim! Burn!—and little else. Their action sequences are boring, and they have basically no characterization to speak of. Their appearance also raises a lot of uncomfortable questions, like how could such a bloodthirsty, disorganized fighting unit actually function?

The answer is barely. This novel really explores in flashback and discussion the degradation of the legion and how costly their every minor victory has become. A number of the characters spend a fair amount of time trying to come to grips with how precisely they can keep fighting when their extreme lack of discipline leaves them exposed and vulnerable any number of ways. The action and training scenes demonstrate this well and between that, the characters’ discussions, and a healthy dose of the Warp, it’s an interesting progression that renders the 40k world more plausible (well, within the universe’s basic assumptions).

More importantly, Angron makes a good run here to be the most tragic of the Heresy characters. That’s a big claim to make given Horus, but the novel makes it pretty credible. My favorite though is Khârn. He’s fascinating, and realizing that in the first couple pages is basically mind blowing given that I’d previously never found him particularly interesting. He has a band of friends, many of them with their own solid characterizations—especially Argel Tal of the Word Bearers—and he has doubts, so many doubts. Khârn’s so compelling, I’m almost motivated right now to go model up some Chaos Marine champion to represent him (I’m only 50/50 on his actual model). Khârn’s depth and wisdom come across so well, it only highlights his glee and fury in battle. The first, brief appearance of his catchphrase at a desperate moment is chilling: Kill, maim, burn. Betrayer manages to make all of these utter villains extremely sympathetic and then next chapter they’re turning your stomach as they torture and murder with abandon, an excellent feat of writing.

Also excellently done, for the book that had every possibility of being the least humanized and the most purely testosterone driven given its very male lead legions and characters, there are a number of solid women characters. In particular, Captain Sarrin of the Conqueror has a lot of pages and comes across strongly. She’s key in manufacturing one of the standout scenes mentioned below, has a number of welcome interactions with her friend Khârn in the heat of battle, and it’s actually really cool to read with what glee and skill she goes about fighting the Imperialists. In the grimdark future there is war and blood for everyone, not just men.

Fight!

As discussed regarding Know No Fear, 40k and especially the Heresy series has a ton of potential depth to it, and it’s the more character-study oriented novels that are the best. All too often though they devolve into purely extended action sequences, as that novel does. Here though a perfect balance is struck. The action and character studies are so interwoven throughout the text, and often set within each other, that Betrayer never becomes a drawn out, boring slugfest, nor does it ever slow down and become purely dialog and thought with no chainswords or powerfists. In terms of the technical execution of the plot and characters, the text’s arrangement is really well done.

Great Scenes

On top of all the overall excellence, the novel has a large number of great scenes. Just a few of the most memorable, holding back the details:

- Lorgar’s desperate battle to retrieve Angron, and the latter’s desperate struggle to then save the former. This is the best primarch battle scene I can recall. Forget inhumanly fast sword strikes and mega-punches. There are goddamn vehicles being thrown like toys, and it’s not the least cheesy.

- The legion’s censure of Delvarus after the battle of Armatura. This opens with a great tense hangar bay standoff, once that captures that might alone is not always right, then pages later comes back with a darkly beautiful scene of fraternity, regret, and forgiveness.

- Lhorke’s remembrance of Khârn and Argel Tal in the gladiator pits. It’s a touching view of two soul brothers, ultimate warriors not yet mindless death machines, and has a rare touch of fun and mirth among a life of constant war.

- Lorgar and Angron discussing the latter’s pre-heresy fight with Russ. It has a sadness and quiet to it that’s heartfelt, with Lorgar pained because Angron doesn’t understand, and Angron pained because he does but can’t, shackled and crippled by his past.

Summary

Basically, go read it. A fair bit of Heresy background and 40k foreknowledge is required to really appreciate everything. Even having read a bunch and knowing a lot of 40k lore, even I wish just a little that I had read more of the Heresy series before reading this to catch all the references and character history. But it’s got depth and action to spare so this is a minor concern. Betrayer is an awesome novel that every 40k fan should really appreciate.

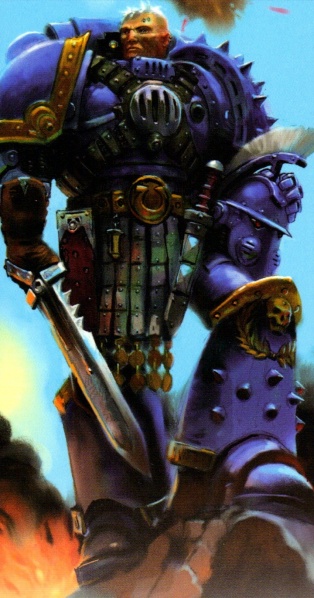

Update: Total sidenote, if the Khan model looked more like this conversion I’d be all about it. The official model though is just a little to goofy and busy looking. By absolutely no means the worst of the older GW sculpts, but after this read I really hope he gets an update or Forge World model sometime to be a bit more serious and dramatic.

Last night and this morning I read the nineteenth book in the

Last night and this morning I read the nineteenth book in the