![]() This is part of a series of notes on the development of Gold Leader, currently being shopped around to game portals.

This is part of a series of notes on the development of Gold Leader, currently being shopped around to game portals.

Themes

As discussed previously, one of the main inspirations for Gold Leader is Ender’s Game. One of the things that really grabs me about that story is not actually explicitly present in the book much at all: The fleet. Somewhere, way out in the black, there’s a whole host of ships and crew actually prosecuting the war, carrying out seemingly arbitrary orders from command, fighting and dying. Lots of those people are undoubtedly very much necessarily just wrapped up in surviving their little part of it while all sorts of maelstrom swarms around them.

Another largely implicit aspect in the story is the notion of a grand slam strategy: You’re on the brink, about to lose everything, and your only chance is to fight through incredible odds and deliver a knockout blow from out of nowhere to completely reverse the momentum and crush the enemy at their strongest. You bank everything on the hope of hitting a grand slam. The ability to explore and embody this kind of attitude and situation is something that has always, always drawn me to gaming. You can see it right up under our logo in the main motto of Rocketship Games: Fortune favors the bold.

Those two themes are what I had kicking around my head motivating Gold Leader. Now, it’s a classical shooter, so story isn’t really a big part of the draw. Further, I quite consciously worked to keep it strictly focused on the action: No cutscenes, no animations, no dialog, just action. The closest thing to a cutscene is the tutorial component at the start, literally ten seconds long as you play with the controls. There were many reasons for that design approach, including:

- I was purposefully working toward a retro feel to go with the art, and fancy cutscenes and elaborate story definitely do not say “retro shooter.”

- I absolutely did not want to develop more art, to support storyline or otherwise, and walls of text don’t really work that well in faster paced games.

- I myself mostly play videogames as a few minutes’ diversion while waiting for a download or compile, or thinking about next steps. There’s probably a lot of people out there like that in the Flash game audience. Those minutes are precious, and need to be spent on gameplay.

Between the retro feel, art limitations, and gameplay time maximization, I wound up working toward a really minimal artistic aesthetic—a super stripped down in-game UI, very basic text updates, etc. The story line is almost completely invisible.

Plot

But it is there. Here’s the basic plot:

- You’re a starfighter pilot, just one person lost among a huge conflict.

- Your ship travels through farspace under centralized control while you’re in some kind of cryo stasis. Upon arriving at a mission/target, you’re just warmed up, woken up, and thrown into it with almost no background.

- The mission that opens this game game seems fairly standard at first, picking away at an enemy sensor grid.

- As you clear the grid though an incoming invasion fleet is discovered.

- The invasion is disrupted. Seizing the moment, your faction presses the attack while the enemy is over-committed to the now-failed invasion.

- Your faction throws everything into the thrust, but only you make it through to the critical showdown with the enemy’s command and your chance to win the whole conflict in one small blow—the grand slam.

- You and the other pilots are all clones, possibly not even recognizably human or able to exist outside your ship, just organic—or not?!—combat processors. This is all you ever do, hero of the galaxy or not. You’re put back into stasis and farspace to the next mission.

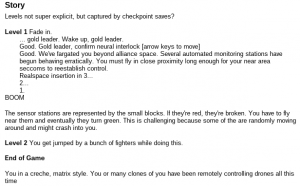

A lot of this is sketched out in some of my very first design notes for Gold Leader:

Implementation

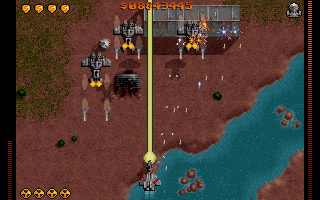

How all that shows up in the game is not very prominent, but sub-consciously shapes the experience. These are some of the ways that narrative is captured:

- The starting tutorial is very much that sequence: You’re woken up out of farspace and thrown into a mission.

- The “mission text,” the unadorned white text as opposed to the boxed tutorial texts, is all ostensibly central control telling you what to do, wired right into your mind.

- The mission objectives vaguely carry the storyline above, and definitely carry a feel of progressing deeper into enemy territory.

- There are no explicit levels or mission breaks, just brief quiet periods to recover before the next phase. This keeps the momentum going and carries the feel of rushing to opportunistically exploit an unexpected opening.

- Throughout the game there are other pilots from your faction that come through, helping you out but mostly doing their own thing. This represents that notion of you being just a cog in a larger conflict. Further, their number and frequency increases as the game goes on, following that idea of your faction throwing resources at an opening, and everyone trying to get to the central command.

So, the narrative is there, and hints of it really shape the game. More importantly, having just a bit of a narrative helped me stay on track and develop a coherent game. Having a story I was invested in, that I wanted to develop, was also a critical motivation in finishing the game, even though it’s almost completely submerged in the final product.