Early this year I picked up Antony Beevor’s 2012 history book The Second World War on the recommendation of Ta-Nahesi Coates (here and here), and recently I finally read it. The book is actually somewhat complex to evaluate. Most reviews (NY Times, Guardian, etc.) seem to have been positive but not super excited about the effort. At first I agreed but now feel it to be an excellent book within its audience, goals, and necessary limitations. It is certainly by far the best single-volume history of the entire war that I have encountered.

Early this year I picked up Antony Beevor’s 2012 history book The Second World War on the recommendation of Ta-Nahesi Coates (here and here), and recently I finally read it. The book is actually somewhat complex to evaluate. Most reviews (NY Times, Guardian, etc.) seem to have been positive but not super excited about the effort. At first I agreed but now feel it to be an excellent book within its audience, goals, and necessary limitations. It is certainly by far the best single-volume history of the entire war that I have encountered.

Audience

The first tough question to evaluate is who exactly is the audience for this book? I found it to be a fast read but at almost 800 pages (excluding bibliography) it is probably a significant commitment for many people. Beyond that, it is mired in details of dates, titles, numbers, troop dispositions, and so on. Not getting bogged down in these while also not missing important notes or losing track of the overall thread and continuity could be challenging for younger or less experienced readers. Similarly, those only marginally interested in the topic could potentially be turned off by its sheer length and the volume of nuts & bolts minutia.

From a different angle, those who are very interested and have read a lot about the second world war may at times be a bit confused about what they’re supposed to get out of the text. Surprisingly given the many decades between the event and now, Beevor does actually present a number of new revelations that have only recently entered public knowledge. But the overall text is very light on analysis and motivations, and the basic detailed history already well covered in innumerable texts and documentaries, so for those well versed in the topic it’s not always immediately clear for what or whom the book is intended.

Ground History

Eventually though I came to understand the book as a detailed ground history across the entire scope of WW2. At that it is impressively detailed yet readable. If you want to get or ensure you have a comprehensive feel for the military movements across all of the half dozen or so major fronts in the war, this is the text you want. In this way it’s useful for both those unfamiliar with the topic, and those who want to cement their knowledge. Beevor himself notes that he wrote the book because, having written several other books about particular battles and topics, he thought his own knowledge was patchy. As one example for me, though broadly familiar with the fighting and politics in China, the overall picture and the specifics of the intense jockeying for post war positioning between the Nationalists and the Communists is much more clear now.

That leads directly to the first place the book really excels. It covers the whole war. From an American perspective this makes it a particularly useful text. All of the early movements in Czechoslovakia and Poland, the critical nature and immense scope of the Eastern Front, to the Italian and African campaigns, to the overlooked but long-term incredibly important China and Southeast Asian theaters, everything’s covered. This isn’t a typical American history in which the war is largely fought and won over 4 days (e.g., Pearl Harbor, D-Day, Iwo Jima, Hiroshima). The Battle of Britain, for example, gets a reasonable but notably succinct summary, which makes much sense upon reflection: That conflict’s extremely well covered elsewhere and, though immensely important, actually very simple and straightforward in the basics. In contrast, a tremendous number of pages is spent on the sprawling, complex, and ultimately world defining Eastern Front, a theater that has little detailed recognition and understanding among western audiences. As another personal example, though relatively very aware of the scope of Soviet and German losses, and the sheer brutality of that conflict in particular, the book adds a layer of general understanding to the overall sweep and movement of the war. It also clarifies a number of details, e.g., the final Soviet and US run-in to Berlin, a relatively small but ultimately very consequential period of time of which it turns out I did not understand the basic mechanics well at all.

To the point about brutality, that’s where the book really excels. It’s important to recognize and understand that the text comes from classical, traditional military histories of major conflicts. Though the coverage is reasonable for the book’s purposes, Beevor only tangentially discusses the politics, economics, and scientific enterprises that are the real heart of the issue in the war. If you’re looking directly for analysis, contextual understanding, and long term consequences, as I was going in, this is not that text. It starts from a focus on armies and generals and combat and stays focused on that kind of ground level details of the war.

But Second World War goes well beyond that class of ultimately unenlightening typical military narrative in being very comprehensive about what it means to be a “detailed ground history across the entire scope of WW2.” There is extensive discussion about the suffering of individual soldiers and the conditions they fought under. More importantly, despite the book’s military history origins, Beevor places equal focus on the devastating, incomprehensible levels of civilian suffering, elevating the text well above most generic WW2 histories. Both abstract issues and numbers as well as a wide array of personal letters and diaries are used to document that aspect of the war as extensively as the military maneuvers. It documents well topics like the courses of both Nazi and Soviet genocide; unbelievable losses of life to famine in China and Southeast Asia; and the awful, unrelenting destruction and poverty of the churned middle ground between Russia and Germany.

The book also puts special attention to the near universal suffering and persecution of women on all fronts. To a large extent this is not a revelation to any who have read about or are otherwise familiar with events like the Rape of Nanking, or, indeed, has thought at all about the likely consequences of an extended, to-the-death, wide scale war, particularly one with heavy racial and nationalist undertones. But this is a topic still under-discussed and poorly recognized, e.g., among all the pop fans of WW2 enabling the thriving history-entertainment industry. Beevor also pushes that understanding into all theaters and forces the unavoidable conclusion that this is not an issue of ad hoc atrocities or confined to just one region. The text makes clear both the overwhelming extent and horrifying nature of female suffering across the entire worldwide conflict, as well as its execution as a systematic, condoned, even organized undertaking.

Details and Revelations

As has been widely publicized in other reviews, the book does work to raise popular awareness of a number of relatively new revelations. Some of these include:

- A somewhat notable assassination of a Vichy French official, not previously understood to be organized by the British and US intelligence services.

- The treatment of Soviet women by the Soviet army itself, the uncovering of which I believe comes largely came from Beevor’s own work for his more focused book Stalingrad.

- Most talked about, the overwhelming effect of starvation on Japanese forces—60% of all casualties—and the consequent systematized, rampant cannibalism among its armies. This has only recently been captured by Japanese historians after being suppressed by the Allies in order to not traumatize families of POWs at home.

Just given the breadth of the material, the book necessarily has to make concessions to brevity. Many reviews have noted that compared to Beevor’s previous books there is less emphasis on personal accoutings. Still though, I think there is a good amount of that, with many of the scenes, particularly of refugee and other civilian suffering, told through diaries and letters.

Similarly, in many ways the book relies a fair bit on extensive knowledge of the war. For example, there’s a line in a meeting with Churchill about Stalin’s blue pencil that has no resonance without knowing his original role as an editor. As a more important example, I’m not sure the book adequately relates the technical limitations forcing the Allies’ unescorted bomber tactics in Europe until the development of the Mustang fighter with its combination of range and capability.

Some of these choices though come directly on the book’s focus on the ground, and are reasonable once you’re in line with that approach. For example, there’s an interesting paragraph or so about driving in the London blackout, and the thousands of pedestrians killed by vehicular accidents in its early months. In contrast, the massive, world-changing Manhattan Project appears almost out of nowhere only when the Enola Gay finally takes off on its fateful mission, with just a few references beforehand as it came up in conferences among the Allied leaders.

To me, among the more notable non-ground details Second World War does make within its comparatively limited focus on the leadership and behind-the-scenes politics, are those about Roosevelt. Beevor paints a clear picture of his anti-Imperialist leanings, capturing how that defined US priorities, frustrated Churchill, and would have resulted in an immensely different world view had he lived longer. For example, it discusses in passing references how he was staunchly against the French resuming occupation of Indochina (Vietnam) after the war. Though it’s hard to predict how that would change history, clearly it would do some immensely. In a related vein, it is also made clear just how poorly Roosevelt understood or cared about post-war implications, how fixated on them Churchill was—often in strongly Imperialist tones—and how masterfully Stalin and Mao Zedong out-maneuvered both of them at that shadow conflict.

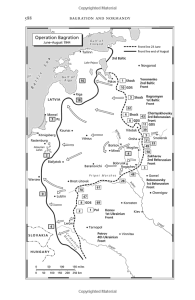

Maps & Endnotes

As a minor note, the first half or so could use a few more maps and diagrams, but I attribute that to Beevor being English and assuming more familiarity with European geography than I, and presumably most Americans, possess. By the time things get really hairy and entangled in the second half of the war, much of it in the less familiar eastern Europe and Pacific, there are notably more diagrams complementing the text.

On another minor note, the book employs extensive endnotes rather than footnotes. I assume this was done to make the book seem more pop history and accessible to people flipping through in a bookstore. It’s very unfortunate however as it leaves you constantly wondering “Who said that?” and “Where is he getting that from?” for both quotes and newer revelations, giving the book just a slight feel of unscholarlyness and speculation that it doesn’t deserve.

Summary

All in all, I highly recommend Beevor’s The Second World War, contingent on being clear or what the book is trying to do and who it’s for. It’s not a light history, and probably requires either a fair amount of motivation or an experienced reader; e.g., I have mixed feelings about recommended it for typical high schoolers. Little time is spent on politics, economics, context, or consequences. Similarly, there is little analysis or direct relation to modern events. Beevor himself is careful in interviews to proscribe against the popular inclination of politicians and pundits to draw untrue and misleading parallels to WW2. But the book is very good for those with a limited understanding of the basic mechanics and movement of the war, or those who want to ensure their understanding.

Beyond that, the book is excellent at is portraying the “truth” on the ground. Most notably, it is faithful to and evenly balanced across the entire scope of the war—from the Pacific to the Eastern to the Western fronts—as well as both the military and civilian effects, particularly for women. The scope and abstract numbers almost prevent a felt understanding, but there is enough detail and personal accounts to ensure a tangible picture of the colossal scale of human suffering entailed.

Ultimately that presentation is worthwhile in its own right, and enables the kind of thought and analysis from which the book largely shies away. For example, through much of the text the US and English come off fairly well in ethical terms, with most of the atrocities, particularly mass rapes, enacted by the Japanese, Germans, Soviets, and French. Especially at the end though there are disappointing lapses by US forces in the occupation of Japan. Combined with the deep picture from the rest of the text of the relatively limited contact up to that point between US forces and civilians, particularly non-Europeans, it is difficult to not then take that behavior as near-universal and those two Allies’ comparatively clean records coincidental rather than actually exceptional.

That is exactly the sort of observation a good raw history should support. Second World War largely refrains from imposing its own conclusions, but does enable that kind of thinking across a number of topics: Civilian suffering, modern total war, justification for the atomic bombings, post-war geopolitical consequences, and so on. For that I highly recommend it.

Continuing my

Continuing my

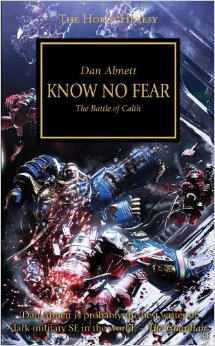

Last night and this morning I read the nineteenth book in the

Last night and this morning I read the nineteenth book in the