Finally, following up on my movie and music highlights, for me 2013 was also a great one for reading. Notes on these and many more books are in my 2013 reading log.

Short Stories

I generally read most of the short stories posted on Tor.com; some highlights from this year:

Terrain. Valentine. Bit of western, bit of sci-fi, with a strong character focus.

Terrain. Valentine. Bit of western, bit of sci-fi, with a strong character focus.- Faster Gun. Bear. More western + sci-fi.

- The Things that Make Me Weak and Strange Get Engineered Away. Doctorow. Good story of programmers and the state.

- Running of the Bulls; Cayos in the Stream. Turtledove. Hemingway as a dinosaur… and as a Nazi submarine hunter.

- Angel Season. Petty. Fantastical hunting.

- Last Train to Jubilee Bay. Wallace. Sad dystopia.

- The Mongolian Wizard; The Fire Gown; Day of the Kraken; House of Dreams. Swanwick. A good series of connected stories, sort of inter-war period fantasy. Will make a good genre novel when all done.

Non-Fiction

History books had a surprisingly great year:

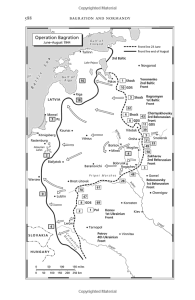

The Second World War. Beevor. This book is almost overwhelming, but in the end does a comparatively comprehenisve, emotive job of capturing what World War II meant on the ground, particularly for women and civilians. It also gets credit for appropriately shifting much of the focus away from the US and UK.

The Second World War. Beevor. This book is almost overwhelming, but in the end does a comparatively comprehenisve, emotive job of capturing what World War II meant on the ground, particularly for women and civilians. It also gets credit for appropriately shifting much of the focus away from the US and UK.

What Hath God Wrought. Howe. Almost certainly the best history book I’ve ever read. It captures both the sweep and the telling details and personalities of the period, while also being imminently relatable to the modern day. Even setting aside its staging for the Civil War, Howe provides tremendous background to understanding huge pieces of modern America, such as the current Republican party and its policies.

What Hath God Wrought. Howe. Almost certainly the best history book I’ve ever read. It captures both the sweep and the telling details and personalities of the period, while also being imminently relatable to the modern day. Even setting aside its staging for the Civil War, Howe provides tremendous background to understanding huge pieces of modern America, such as the current Republican party and its policies.

Fiction Novels

Apparently I read a lot of science fiction… Notables for 2013!

Mechanique.

Mechanique.

By Valentine. This is a beautiful steampunk story about a traveling circus. Valentine’s short story Terrain is actually on the list above as well, and what they share is a real depth of characterization, original elements, and being sci-fi/fantasy/steampunk without forcing the issue. Mechanique takes it a step further be being really impressive stylistically. I could see many people being turned off by its poetic, lyrical style, extremely loose storytelling, weird punctuation, and extended asides, but I thought it was incredible in both presentation and characters.

Betrayer.

Betrayer.

By Dembski-Bowden. You almost certainly need to be into Warhammer 40,000 in one way or another to appreciate this novel. But within that milieu it’s excellent, probably the best in the Horus Heresy series, and that has a number of good, somewhat deeper tales. Betrayer does an amazing job of taking a historical plot with known outcomes, a bunch of previously boring & flat characters, and making it all really compelling.

Red Mars. Blue Mars. Green Mars.

By Robinson. This trilogy is hard to read. I almost put it down at a number of points, and skipped massive swaths of pages. In general I am definitely not on the Robinson hype train. Here he spends an insane amount of time detailing the geological processes and features at work. But the whole work is incredibly detailed, well thought out, and does have serious characterizations that make it worthwhile. Despite being literally and metaphorically being buried in rock in both the story and text, a whole bunch of them still manage to stand out brightly as people, with complex interactions and motivations. If you want to read an in-depth historical account of the colonization of Mars and the fascinating people involved, decades before it might even begin to happen, these are your books.

Cloud Atlas.

Cloud Atlas.

By Mitchell. Perhaps due to being a programmer, I was not as blown away as many reviewers by the simple recursive structure of the text, but it is an elegantly constructed piece of art. The handoffs are subtle and work nicely. More importantly, several of the six sections are incredible, and the rest are solid. The early 20th century Belgian components are amazing in terms of feel and characterization. The Sonmi sections are very excellent as well, really capturing a near future with a completely different though very plausable world, and a great character and their development. Highly recommended. Don’t watch the movie first; I watched it afterward and was not only disappointed, but feel it would ruin much of the suspense.

King Rat. Perdido Street Station. The Scar. Railsea. The City and the City.

By Miéville. Having only read two of his books previously, I went on a serious Miéville tear this summer. All of these are excellent. The Scar and Perdido Street Station are related but don’t really depend on each other. The latter gets all the press and has a stronger morality quandary as a closing central thread, but I thought the former a better story, and definitely more taut. They’re both equally as deep though and have as strong characters. Scar carries a classic south seas nautical pirate adventure feel with fantastical elements, while Perdido brings those elements to European continental political revolution intrigue.

King Rat is an earlier effort and that shows the comparatively somewhat short length and relative simplicity, but neither is by any means a bad thing. The book’s been overshadowed by his later successes, but King Rat is a standout in the somewhat crowded modern-fantasy-London genre. As with many of Miéville’s book, the styling and language is unique and excellent.

Railsea is essentially what you get if you take Moby Dick, cut out all the rampant unnecessary bloat, and place it into a completely landlocked steampunk world. The ending’s a bit weak and overt, but the opening sections introducing the world and characters are just plain fun storytelling. Great young adult adventure tale.

Railsea is essentially what you get if you take Moby Dick, cut out all the rampant unnecessary bloat, and place it into a completely landlocked steampunk world. The ending’s a bit weak and overt, but the opening sections introducing the world and characters are just plain fun storytelling. Great young adult adventure tale.

The City and the City was particularly meaningful for me having spent last summer in Prague. It is essentially a modern fantasy novelization of a personification of the Eastern Europe/Western Europe border, and has a great noir feel with fantastical elements.

The City and the City was particularly meaningful for me having spent last summer in Prague. It is essentially a modern fantasy novelization of a personification of the Eastern Europe/Western Europe border, and has a great noir feel with fantastical elements.

Altered Carbon. Broken Angels. Woken Furies. Th1rte3n. Market Forces.

By Morgan. These are all related, and should be read in chronological order of publication (as listed here).

The first three of these are explicitly a trilogy. Altered Carbon is incredibly good cyber-bio-noir that pokes at some really good, serious ideas about the future. Broken Angels and Woken Furies aren’t quite as strong, but they’re both very good science fiction featuring some great settings. More importantly, especially toward the end they start to develop more refinement to the Takeshi Kovacs lead character, lending some introspection to the body-swapping ultimate mercenary-slash-detective. It’s almost offputting that there are major revelations made which seemingly have no later effect, but that actually makes sense and puts another light onto both the character and the world: As he and many other people slip through the decades, what does it really matter?

The other two books Morgan denies as being follow-ups, but they’re much better off interpreted as set in the far past of the Carbon trilogy’s 26th century. Th1rte3n, titled Black Man in Europe, is set somewhere in a future just slightly distant from us and is just strong through and through: Great plot, settings, mystery, sci-fi, and characters. It opens with a classic but well done sci fi spaceship horror mystery and rolls on from there. The commingling of Martian and South American exploitation is excellent and thought provoking. Beyond that, the alternate UK and US titles are no coincidence and quite telling; the story gets pretty hard at racism, exclusion, and genetic modification.

Market Forces is the most uneven of this whole sequence. Set in the very near future it has a basically ridiculous premise straight out of some ’80s SEGA game: Lawyers and businessmen compete for contracts in highly ritualized vehicular freeway combat… I almost had to put it down. Once you get past that though, it’s actually a great profile of the descent of a character, and by the end doesn’t actually seem as outrageous as when it started. There’s a lot here about violence, economics, and the thin difference between.

Morgan’s covers are somehow indeed uniformly terrible, even across all regional prints, except maybe Th1rte3n, but these are all good books. If you had to pick two, go for Altered Carbon and Th1rte3n. I’ve actually been waiting for months to write them up here and recommend them, they’re that good, provided you have any interest in science fiction whatsoever.

Continuing my

Continuing my